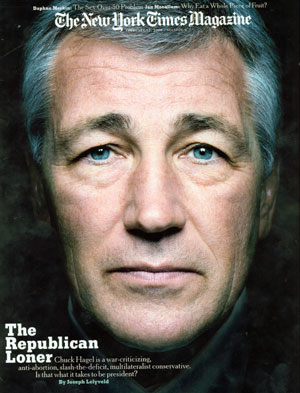

From the New York Times Magazine --------------------------------------------------

The Heartland Dissident

With a bluntness that seems habitual — and more than occasionally strikes fellow Republicans as disloyal — Senator Chuck Hagel started voicing skepticism about the Bush administration's fixation on Iraq as a place to fight the Global War on Terror more than half a year before the president gave the go-ahead for the assault. What the senator said in public was milder than what he said in private conversations with foreign-policy gurus like Brent Scowcroft, the national security adviser in another Bush administration, or his friend Colin Powell, the secretary of state, who thought he still had a chance to steer the administration on a diplomatic course. The Nebraskan wanted to believe Powell but, deep down, felt the White House wasn't going to be diverted from its drive to topple Saddam Hussein. When he rose on the Senate floor that October to explain his vote in favor of the resolution authorizing force — he'd persuaded himself that his vote might strengthen Powell's hand — he gave a speech that would have required no editing had he decided to vote against it. What sounded then to the venture's true believers like the scolding of a Cassandra sounds fairly obvious three and a half years later, which is to say that Hagel's words can reasonably be read as prescient: "How many of us really know and understand Iraq, its country, history, people and role in the Arab world?. . .The American people must be told of the long-term commitment, risk and cost of this undertaking. We should not be seduced by the expectations of dancing in the streets." The president had said "precious little" about post-Saddam Iraq, which could prove costly, Hagel warned, "in both American blood and treasure."

As the months and years wore on, Senator Hagel's public musings on Iraq became less measured, as if his gorge rose a little higher with each day's casualty report. He would say that the White House was out of touch with reality, that the reconstruction effort in Iraq was "beyond pitiful," that he had lost confidence in Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, that we were losing the war and had destabilized the Middle East, that the United States was getting "bogged down" in Iraq the way it had been in Vietnam. Some of these observations flew into print during the 2004 presidential race, and one of them, the "beyond pitiful" line, was seized upon by John Kerry, the Democratic candidate, in his second debate with President Bush. At the Republican grass roots in Nebraska and in the upper reaches of his party in Washington, the senator's candor was not universally viewed as refreshing. His timing was held against him even more than his dissent. ("Maybe his criticisms are valid," a letter to The Omaha World-Herald said, "but why showcase them and lend credence to the liberal opposition?") Obviously, this was not a team player. Some of his closest friends and supporters fretted that he was killing whatever small chance he might have had to be the national candidate he plainly aspired to be. Now — 33 months before a presidential election, two years before the first primaries — his chances aren't merely discounted; he's seldom even mentioned in Republican circles, as if he has been sidelined by his independence on Iraq.

The fact that Hagel himself emerged with two Purple Hearts from Vietnam, where he served as an enlisted man in the infantry, has often been mentioned in news reports quoting him on Iraq as if memories, or maybe nightmares, dating back to the war from which he still carried bits of shrapnel in his chest were primary and extenuating factors shaping his seemingly irrepressible utterances on the latest intervention, his regular brushes with apostasy. Compelling as it is, Chuck Hagel's history as an ordinary soldier, a grunt from small-town Middle America who grew up to be a senator, is more layered, less simple. Unlike Senator Kerry, he had never been a Vietnam veteran against the war. Unlike his own younger brother Tom — with whom, against standard Army practice on exposing brothers to risk, he walked point in the same infantry unit — he supported that war to the bitter end. The brothers continued to argue about it for another 25 years until the older one's experience of the world as a globetrotting businessman and his autodidact forays into history and foreign-policy discourse brought him to more or less the same place that Tom (now a law professor in Dayton, Ohio, and a Democrat) had reached in instant, visceral reaction to the experience of jungle war.

Chuck Hagel never became a dove, but he became a bird that's nearly as rare in the Republican aviary. He became an internationalist, someone who's capable of feeling intensely about alliances, multilateral endeavors, the value of global institutions; a fellow traveler of the Council on Foreign Relations, a politician who actually reads Foreign Affairs. A singular Great Plains Republican, in other words, who cares about the rest of the world for reasons that don't begin and end with agricultural exports. Tellingly, when he was elected to the Senate in 1996, he was the one new Republican whose first choice for a committee assignment was the Foreign Relations Committee, which had declined steadily in prestige since the Vietnam-era days of a Democratic chairman he sometimes mentions as a role model, J. William Fulbright. An instinctive and unwavering conservative on most issues — in particular, big government and deficits — he was the antithesis of a neocon, a profile to which The Weekly Standard paid backhanded tribute in 2002 when it included him (along with Powell, Scowcroft and The New York Times) in what it called "the axis of appeasement." In the cruelest cut, in that brief period of easy, triumphalist anticipation before the invasion and its turbulent aftermath, National Review put Nebraska's senior senator down as Senator Hagel (R., France).

If his tendency to fall out of step with the administration and to ignore talking points sent around by the Republican National Committee has been most conspicuous on foreign affairs, he has been just as much his own man on domestic issues. ("Nothing in my oath of office," he recently told reporters, "says, 'I pledge allegiance to the Republican Party and President Bush.' ") The senator from Nebraska broke with his party leadership to vote against the new prescription-drug program under Medicare, the No Child Left Behind bill and a big farm bill stuffed with incentives for corporate agriculture. Each, he felt, was ill conceived in practical terms and unwarranted as an expansion of federal mandates and spending. Only on the Bush tax cuts — all of which he has supported — has he been deaf to warnings about the consequences for the federal deficit. (Though, he says, he'd never take "the pledge" to oppose any and all tax hikes.)

It can be argued, as David Keene, chairman of the American Conservative Union, pointed out, that Hagel has taken a more conservative position than the Bush administration every time he has broken with it on a major issue. Keene's outfit gave the senator a 100 percent rating for his votes in 2003. His lifetime rating for his first eight years in the Senate stood at 85 on the union's scorecard, which translates into baseball talk as better than a .300 batting average. Here's a certified conservative, then, who has regularly decried partisanship — even during the do-or-die Florida showdown in 2000, when he suggested a statewide recount — and doesn't go on about "values." (He has them; most people have them, he says, so seeking to impose one's own values on others isn't right.) A regular churchgoer, an Episcopalian who sends his two children to Catholic school, he thinks religion is a private matter. In today's partisan climate, what are so-called movement conservatives to make of such a man? Facing conservative audiences, he struggles to overcome the suspicion that he's unpredictable, a throwback to old-school G.O.P. moderation, a dissident.

That suspicion isn't altogether baseless. Hagel is typically more interested in facts on the ground than doctrine. For instance, while he's reliably anti-abortion — earning a legislative rating of 100 from the Christian Coalition in 2004 — he's ready to think through an issue that's a litmus test for some religious groups without bothering to figure out what it might cost him. I asked whether he, like the Bush administration, resisted assistance to groups that distribute condoms in the fight against AIDS in Africa. The senator didn't have a potted answer, so I got to watch him think. He said he thought the United States should be careful about the conditions it lays down; he also had no problem with contraception, he said. As far as I could tell, the answer had come through unfiltered, without political calculation.

None of this easily adds up to a mandate to seek the presidential nomination of the Republican Party, even if you're the senator and happen to believe strongly that the party has lost its way at home and abroad. Hagel leaves no doubt that this is how he feels, even when he's trying to hold in check the reflexive, often surprising directness that makes him a favorite on Sunday-morning TV gab shows. ("I sometimes question whether I'm in the same party I started off in," he will say. Or, "This party that sometimes I don't recognize anymore has presided over the largest growth of government in the history of this country and maybe even the history of man.") Though he can be scathing about the Bush administration's policies, he almost always avoids direct criticism of the president (except to express astonishment that a Republican could go five years without vetoing a single spending bill). He also doesn't praise him.

The problem with making a revival of old-time values of fiscal restraint at home and restraint in the use of American power abroad the starting point for a race is that it presumes a level of disillusion that latter-day Republicans — the people who'll vote in primaries in 2008 — show little sign of feeling. Even when George W. Bush was bottoming out in national polls, Republicans gave him a favorability rating of about 80 percent. Nevertheless, Chuck Hagel is still thinking hard about running, even though party professionals place him at the back of the pack; even though running would more than likely entail standing against John McCain, whom he supported in 2000, one of only four senators to do so, and his closest neighbor in the Russell Senate Office Building. McCain, a former naval officer who calls Hagel "Sergeant," is not only another Vietnam vet and therefore a soul mate, he's also the member of the Republican caucus, Hagel will say even now, who has the best shot at giving the party a new direction and balance. But, among other things, they've differed on Iraq.

Before he can worry about potential rivals, Hagel says, he has to look into himself to see if he has the mettle and ideas needed to offset the disadvantages that make also-rans of senators who discover their Washington experience and voting records only handicap them when they go up against fresh-faced governors able to boast that they're not part of the problem. A veteran of previous administrations who's in fairly regular touch with the senator said he admired him for his seriousness and "brain power," his fresh and independent approach to the toughest issues in foreign affairs especially, but hadn't yet detected the "single-minded zeal" that marks successful candidates for the highest office. Judged as a possible president, the former official said, Hagel could be considered impressive, but judged as a possible candidate, he seemed "basically a dilettante."

Michael McCarthy, an Omaha merchant banker who once made Chuck Hagel president of his investment bank and is now among his most stalwart backers, said he doubted that Hagel could get very far in presidential politics. But he didn't rule out a race. "Chuck's a complicated guy," he said. "He thinks with the clarity of an actuary but decides with the heart of an Irishman, so I don't know where at the end of the day he'll land. He sure as hell can overcome doubt and decide to go where his heart tells him to."

The issue that could propel him into the campaign is not one on which candidacies normally rise or fall. Call it the issue of competence. Hagel is a small-government man who believes government can be made to work, that it should be managed well. And while he doesn't exactly say that the current administration has been careless and incompetent, that theme cries out between the lines of much of what he does say. After the botched reconstruction of Iraq and the nonchalant response to the hurricane on the Gulf Coast, it's not a stretch to hear an implied critique when he says, as he did talking to local reporters in Ames, Iowa, last fall, that the president should "stay focused on governing the country" and "reach out to Congress." It was a polite way of saying the president had done neither. Later, in an interview in his Senate office, I asked how he thought history would judge George W. Bush. He said it would be "rather harsh" if things continued for the next three years the way they've gone for the last five. The verdict would depend on Iraq, "on what happens to the deficit and the debt and some of these issues we've not paid attention to over the last five years." His list of "these things" is familiar and long, in both foreign and domestic affairs. It includes global warming, an issue Hagel has fastened on ever since sponsoring a Congressional resolution with Senator Robert Byrd, the Democratic elder from West Virginia, that opposed the Kyoto Protocol because it placed no caps on emissions by rising industrial powers like China and India; on climate change, he feels strongly, the Bush White House has muffed a chance to demonstrate that conservatives can say something more useful than no, that they can actually advance ideas and programs.

An earnest legislator who seeks to legislate across a broad range of big, looming issues, Hagel managed to pass a couple of bills that offered corporations loan guarantees and tax breaks to come up with processes and devices that limit greenhouse gases. Unlike the administration, he actually got to the point of drafting a Social Security reform bill. And finding allies across party lines — Tom Daschle of South Dakota in the last session, Barack Obama of Illinois as well as a fellow Republican, Mel Martinez, in this one — he shaped a package of immigration-reform bills that aim to create a system that's not dysfunctional: tough on illegals coming into the country, not impossible for illegals who are already here and manageable for employers who want to obey the law. (To understand why a Nebraska senator might interest himself in immigration issues, it's enough to visit an Omaha meatpacking plant. On the cutting floor, the universal language is Spanish.)

"Competent Governance" may not be a slogan to set Republican pulses racing; and pledging to be "a uniter rather than a divider" and to be "humble" in dealings with the rest of the world are, in any case, themes that have already been tried. Recently, instead of the pallid term "competence," Hagel has been talking about "competitiveness" as he tries to find language that will give some urgency to his sense that the party in power, his party, has failed to address issues that are just as urgent as terrorism.

t may say something about the politics of "tending to the base" that Chuck Hagel appears today to be the longest of long shots, for he's a politician with attributes that are supposedly sought by the people who package candidates and by the casual, least opinionated voters for whom they package them — those who drift back and forth between parties, actually deciding elections. The packagers like candidates with what in the trade is called "a good story." Hagel's story wouldn't have to be reshaped by an editor in a cutting room. Voters claim they look for someone who comes across as genuine, talks straight, means what he (or, for argument's sake in the coming campaign, she) says, even if they're not in perfect sync with the candidate on issues. Hagel has that quality of going beyond plausibility to believability, possibly to a fault (in that it sometimes comes with a senatorial tendency to tell you more than you wanted to know; a related liability is that he likes to write his own speeches, which he weighs down with lessons of history and high-minded quotations from his reading, as if he feels a need to show how studious he is).

t may say something about the politics of "tending to the base" that Chuck Hagel appears today to be the longest of long shots, for he's a politician with attributes that are supposedly sought by the people who package candidates and by the casual, least opinionated voters for whom they package them — those who drift back and forth between parties, actually deciding elections. The packagers like candidates with what in the trade is called "a good story." Hagel's story wouldn't have to be reshaped by an editor in a cutting room. Voters claim they look for someone who comes across as genuine, talks straight, means what he (or, for argument's sake in the coming campaign, she) says, even if they're not in perfect sync with the candidate on issues. Hagel has that quality of going beyond plausibility to believability, possibly to a fault (in that it sometimes comes with a senatorial tendency to tell you more than you wanted to know; a related liability is that he likes to write his own speeches, which he weighs down with lessons of history and high-minded quotations from his reading, as if he feels a need to show how studious he is).

A Republican campaign pro, after an astute analysis of Hagel's virtues and drawbacks, zeroed in on a factor no one else had mentioned, one that he seemed to feel said a lot about the reason Hagel's party hasn't warmed to him, and therefore about his limited prospects.

"He doesn't have a happy face," the pro said.

That's something a good story — real life, in other words — can do to a person.

It's not that Chuck Hagel can't flash a smile. I watched him in Iowa patiently pose with members of his audience who lined up to have their pictures snapped. The strain started to show only after seven or eight little flashes. He also laughs easily, at his own jokes and others'. A tireless networker and campaigner who revels in small-town parades, he never seems to need prompting to attach a name to a face. But his gregariousness, the habit of a lifetime, takes concentration. When he's small-talking his way around a room, he seems to lean into conversations; and his fingers are usually working, if not grabbing elbows or patting shoulders, then knitting themselves together or kneading the palms of his hands, as if typing out signals to his brain to remind him he's on stage. If you had to choose a word to describe him at such moments, it might be "focused," even "conscientious"; it wouldn't be "happy." Later, while he's waiting to be introduced, his roughly chiseled features may look a little tired or pensive but never less than alert. This is a politician who works at his job.

That usually animated, hardly woebegone face has taken more than its share of battering. His nose was broken twice in high school and college football games and at least once more in a fistfight. (There was the fight on a dance floor in Schuyler, Neb., when some players from another school started picking on a pal, and another at a party in Lincoln when he advised some crashers to leave a friend's home.) And there was Vietnam, where the left side of his face was scorched after a mine went off under the armored personnel carrier in which he was riding. Harder to read are the tracings of a difficult childhood, over which Hagel usually drops a kind of scrim to obscure the roughest parts.

If he tells the story of his hard-luck dad, who came down with malaria in the Pacific theater, he's apt to leave out the drinking. And if he mentions the binges, it takes some prompting for him to acknowledge the effect on himself, the eldest of four sons. More often he dwells on the conversion of his German-French father — Charles Dean Hagel, known as Charlie — to the Roman Catholicism of his Polish-Irish mother and the lead role he then took in building a small church in the town of Ainsworth, where Chuck and Tom became altar boys. Or he humorously turns the fact that the family had homes in seven different small towns that describe a loop around Nebraska into a bountiful political legacy, one that makes it possible for him to say it's good to be home again practically anywhere he campaigns in his state.

Hagel, who will turn 60 this year, was born in North Platte, in western Nebraska, less than a year after his parents were wed, and christened Charles Timothy. They then moved north to Ainsworth, where his dad worked for his own father in a lumberyard, loading and unloading trains. When they couldn't get along, he got himself reassigned to a lumberyard in Rushville, farther west. By then the senator's dad had already been hospitalized twice, for polio and for severe injuries sustained in a fall at the Ainsworth yard. When the family caught up to him in Rushville, he was again in the hospital, this time with a broken back, the result of a car crash when he'd been drinking.

"We lived," Hagel told me, speaking haltingly, not relishing the details, "in the basement of this old hotel called the Travelers Hotel in downtown Rushville — downtown Rushville is like two streets — and when Dad got out of the hospital, we couldn't find a house. It was like a furnace room. I mean it literally was a furnace room. I mean we had cots down there. It was all dirty. Mice and everything." After Rushville came Scotts Bluff, farther west, near the Wyoming border; then Terrytown, just across the Platte River, where his dad would be fired for drinking; then, moving east again, York and the basement of another hotel, the St. Cloud, where young Chuck, by now a freshman in high school, bused tables. "It was a little better than Rushville," he said, "but not much."

By then, he was winning notice for his athletic promise and precocious interest in politics. It was 1960, and he was in a Catholic school called St. Joseph's. "I was the only kid in the school who was for Nixon," he said. "The nuns and priests were wild, just completely wild, for Kennedy, and everyone was very upset with me because I had a picture of Nixon on one of my books." It was also about then that he started getting into occasional confrontations with his dad. As he guardedly puts it now, "Some of it was physical." Feeling that he had a responsibility as the eldest, he'd step between his parents when his father, livid with drink, started badgering his mother. I asked whether his dad ever took a swing at him. He paused for a moment, then said, "Yeh, uh-huh." Again he paused. "Well, you wouldn't swing back at him," he went on. "I'd just push him back."

In his steadier moments, the father was hugely proud of his eldest son, attending all his games, forecasting a great future for him and seeming not to notice that he was slighting his next in line, Tom, who was not an athlete. At the end of a year in York, the family moved north to Columbus, the easternmost point in its circuit of the state, about 80 miles from Omaha. There his dad had one more drunken smash-up. Then on Christmas morning in 1962, the Hagel boys were startled by the sobbing of their mom, who'd come home from early Mass to find her husband dead in bed at 39 of a heart attack. Chuck, just 16, imagined he had to fill the void.

n the five years between his dad's death and his departure for Vietnam, the new man of the family was sturdy, attentive to his brothers and rudderless in his own life. His first goal, set by a football scholarship to Wayne State College, was thwarted early on when an injury left him with a pinched nerve in his neck that surgery couldn't correct. He then drifted to the University of Nebraska at Kearney (pronounced Carney) and from there, dropping out on a sudden impulse, to a school of broadcasting in Minneapolis, where he tried to support himself by going door to door near the airport, in an attempt to sign up United Airlines stewardesses for the Encyclopedia Britannica. It would be a smart investment, he'd tell them, for the children they didn't yet have. "Well, I did make some sales," the senator said.

n the five years between his dad's death and his departure for Vietnam, the new man of the family was sturdy, attentive to his brothers and rudderless in his own life. His first goal, set by a football scholarship to Wayne State College, was thwarted early on when an injury left him with a pinched nerve in his neck that surgery couldn't correct. He then drifted to the University of Nebraska at Kearney (pronounced Carney) and from there, dropping out on a sudden impulse, to a school of broadcasting in Minneapolis, where he tried to support himself by going door to door near the airport, in an attempt to sign up United Airlines stewardesses for the Encyclopedia Britannica. It would be a smart investment, he'd tell them, for the children they didn't yet have. "Well, I did make some sales," the senator said.

When his number came up at the draft board in January 1967, he went willingly. And when, after training, he received orders to go to Germany, he requested a transfer to Vietnam. He hadn't been touched by anti-war protests. Where he came from, the feeling was that if there was a war on, that's where a young American soldier belonged. In that reflex, which many would still call patriotic, he briefly found a purpose.

It's unclear to the two brothers today how they wound up in the same infantry squad. Tom, drafted as soon as he finished high school, went initially to a reconnaissance unit up north, where he saw heavy fighting. He put in for a transfer, hoping to get closer to his brother, who was serving in the south. Soon they were on patrol together in canopied jungle near the Cambodian border. Over a period of about four weeks, each got a chance to save the other's life. When the first incident occurred, on March 28, 1968, their squad leader had just taken them off point and moved them to the middle of the column. One of the soldiers who replaced them hit a trip wire, setting off a mine that had been placed in a tree so that it would detonate at face level. Bodies, body parts and shrapnel were blasted back into the ranks as the squad was crossing a stream. Tom picked himself up and looked for his brother. What he saw, he says, was a "geyser" of blood gushing from Chuck's chest. Tom, then only 19, stanched the bleeding and bandaged the wound, only then noticing that he'd been hit himself in the arm. By the time the medevac choppers had taken off the dead and critically wounded, the Hagel boys were deemed well enough to continue on, which meant going off the booby-trapped trail and hacking through thick undergrowth.

Twenty-five days later, it was Chuck's turn to rescue Tom, when their troop carrier hit a hand-detonated mine as it emerged from a village in the delta. Tom had been in the turret behind a .50-caliber machine gun. He was unconscious, not obviously alive, when his brother got to him. The blast had blown out Chuck's eardrums and severely burned his left side, but knowing the carrier might soon explode, he worked feverishly to pull Tom from the wreckage, then threw his body on top of Tom's as Vietcong fighters in ambush sprayed the area with gunfire.

Chuck left Vietnam in December 1968, Tom the following February. Back in Omaha, they roomed together for a time, then followed separate paths to readjustment to civilian life. Beset by nightmares and feelings of guilt that sent him off on binges, Tom had the most to get over, what seemed to be the harder time. He also had the clearest idea about the war, which seemed to him futile and cruel. Before they could get used to their new lives, their youngest brother, Jimmy, was killed in a car crash at 16, yet another piece of Hagel hard luck.

In his reaction to all he'd been through, Hagel mixed repression and a fierce focus on the future. He would do his best to put the war out of his mind, get through his studies finally — he was in his third college — and move on. "I was probably going through something that I didn't quite understand," he acknowledges. "I don't think I'm a person who doesn't reflect, because I do — I reflect on a lot of things — but in this case I wanted to get it behind me. . .I wanted a life." It happened relatively fast. Working part time as a radio reporter in Omaha, he interviewed the only Republican on the county board, John Y. McCollister, who then was elected to the House of Representatives when Hagel was about to graduate, finally, from the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The young veteran asked the new congressman for help finding a Washington job. A month later, McCollister and his wife invited their protégé to stay in their home. Soon his boss was bringing him coffee in bed in the mornings and driving him to work. A year and a half after that, Hagel was his chief of staff, at 26.

"It wasn't very long before he knew everyone on Capitol Hill," McCollister told me. "That's the history of Chuck Hagel. He meets people easily." The subsequent lines on Hagel's dense résumé had everything to do with this talent for getting to know people.

Within 10 years, as Ronald Reagan swept into the White House, he was well-enough connected in Republican circles to be made the second-ranking official of the Veterans Administration. In that capacity, he turned up as one of the main speakers at the groundbreaking for the Vietnam War Memorial. Five months later, in what might be seen as his first declaration of independence, he quit in open protest against cuts in benefits for Vietnam vets, which he'd resisted unsuccessfully.

The resignation opened a new chapter in his life. He would now turn his hand to making money. Cashing in his life-insurance policies and selling his car to his mother and stepfather, he managed to raise $5,000, enough to make him a partner in a batch of new companies that would compete in a lottery for licenses to set up systems for a new kind of telephone that worked without wires. The company he helped found, after stock swaps and the arrival of new partners, grew up into Vanguard Cellular Systems. By the time it went public in 1988, it had become one of the country's biggest cellphone companies, and Chuck Hagel's stake made him a wealthy man. By then he'd traveled to some 15 countries, negotiating with governments, usually unsuccessfully, for contracts to set up wireless systems.

He'd also married and remarried. The first marriage lasted less than two years. The Nebraska Catholic then got to know a Mississippi Baptist, Lilibet Ziller, who handled press for the House Veterans' Affairs Committee. Their search for a church where they could both be comfortable led them to St. John's Episcopal Church across from the White House, where they now worship and where their two children were baptized and confirmed. (Hagel realizes that if he were to try a national run, he might be called on to explain his choices in religion to Christian groups that are part of the conservative coalition his party has fused together. He doesn't especially like the idea. "I don't question or critique any other politician's style, but I know who Chuck Hagel is," he said. "I know what fits me, and I know what fits my wife. Religion is important to us, spirituality is important, but it's also private.")

His financial independence eased his return to the political sphere and made it only a question of time as to when he'd run for office. He toyed briefly with the idea of running for governor of Virginia, then returned to Nebraska in 1992, going to work for Michael McCarthy as an investment banker. One of the companies he looked after, American Information Systems — later rechristened Election Systems and Software — manufactured voting machines in partnership with The Omaha World-Herald, the state's biggest daily.

It's sometimes said that Nebraska has two Republican parties, one of which calls itself Democrat. That party had won every Senate race for two decades when Hagel started driving from town to town in 1995 to make himself known. In a state with fewer than a million voters, personal contact matters. Dick Robinson, who runs a steel company in the town of Norfolk, said he'd never heard of his visitor when Hagel dropped by to ask for his support. Ten years later, in his skybox at the always-sold-out stadium in Lincoln where the University of Nebraska plays football, Robinson seemed glad to have a distraction from a game the once-indomitable Huskers were giving away to Oklahoma. "It was great to meet a politician who could look you in the eye and say, 'I disagree,' " he said. "We've been fast friends ever since."

Although their state is one of the two or three most lopsidedly Republican in presidential voting, Nebraskans cling to the notion that their wide open spaces — populated by nearly four times as many cattle as people — nurture a spirit of political independence, an indifference to partisanship. Bob Kerrey, a Democrat who couldn't help calling President Clinton "an unusually good liar," is the most recent example. George Norris, a Senate titan for three decades, supported Al Smith in 1928 and Franklin Roosevelt in 1932 against Herbert Hoover while still a Republican, writing an article for Liberty magazine entitled, "Why I Am a Better Republican Than President Hoover."

Chuck Hagel isn't likely to go that far. Having resided full time in Nebraska for only 7 of the last 34 years, he's not apt, in any event, to present himself as a Prairie independent. Viewing himself as a self-made man who started out with nothing besides his own inner resources, he has neither broken with his party nor allowed it to define him. Nor did he wait for his party to decide when it was his turn.

In 1996, in his first race, he took on a Republican attorney general in the Senate primary and won by nearly two to one. In the general election, he upset a popular Democratic governor, Ben Nelson, by a margin of 14 percentage points. Realizing too late that he was trailing, Nelson ran attack ads portraying Hagel as a Washington insider who'd used his connections to enrich himself in the cellphone business. Hagel had earlier resisted demands by Alfonse D'Amato of New York, then chairman of the Republican campaign committee in the Senate, that he order up a series of attack ads by a favorite D'Amato demolition specialist.

Stung by Nelson's barrage, Hagel countered with an ad in The Omaha World-Herald calling them "the most scurrilous and false attacks ever made in Nebraska politics." Not the forgiving sort, he has never quite forgotten his grudge against Nelson, who, for the last five years, has been the state's junior senator. Senator Nelson has since been heard to ask how it could be that he managed to get over a big loss while his colleague has yet to get over a big win.

In the blogosphere, where conspiracy theories enjoy a certain immortality, the scale of Hagel's upset victories in 1996 made him an object of suspicion after the Florida voting fiasco of 2000. Here was a virtual unknown who'd once been an officer of a company that made the voting machines on which most ballots were cast in Nebraska. But these were scanners, not digital counters; paper ballots survived, available for a recount that neither of his rivals sought. (When he ran for re-election in 2002, he won even bigger, capturing 83 percent of the vote, a Nebraska record. Out on the Web, suspicion lived on.)

What Hagel thought he'd showed in his face-offs with Nelson and D'Amato — who'd called him a "prima donna" (and then some) — was that heavy reliance on attack ads wasn't a winning strategy. After not quite two years in the Senate, he put himself up for the campaign committee's chairmanship, sending around a manifesto to his colleagues that promised to thin the ranks of consultants as a step toward cleansing "the political culture in America by 'defining up' the standards of debate, political discourse and campaigns." It was a direct challenge to the leadership, which he accused of running "issueless campaigns." And it flopped. His colleagues weren't responsive to his musings on the state of the political culture. They decided that winning was still "the only thing," voting 39-13 in favor of Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky. Not for the last time, Hagel's position was shown to be lonelier than he'd realized.

He may not have become a leader of his caucus, but, to the likely dismay of the White House, he's also not an outcast. On a personal level, he's still a man who forges connections. In addition to John McCain, he gets along well with the chairmen of his key committees — Pat Roberts of Kansas on Intelligence and Richard Lugar of Indiana on Foreign Relations — and counts Democrats Joe Biden of Delaware and Jack Reed of Rhode Island as among his best friends on the Hill. "I've been in the Senate a long time, and there's nobody I've liked more than Chuck Hagel," Biden told me.

By the time of his loss to McConnell, Hagel had nearly persuaded himself that he felt a fresh breeze blowing in the party from Austin, Tex., which he'd visited in April 1998 for a laid-back overnight at the governor's mansion that included a meandering walk through the gardens with his host, a quiet dinner with just George and Laura Bush, then more talk on an upstairs porch. It was the first real encounter between the two and the most time they'd ever spend together.

He found Bush "a very charming, gregarious person," and when, several months later, on a swing through Nebraska, he was asked whom he liked as the next Republican nominee, he all but endorsed the Texan, citing his name recognition, success in a big state, age and conservative profile.

It proved to be the first time that Bush learned he could not take Chuck Hagel for granted. Before long, John McCain knocked on the Nebraskan's door, divulged his own ambitions and asked his friend to be co-chairman of his campaign. Hagel had to know there were differences in temperament and outlook between himself and McCain, who was more moralistic about international issues, less fascinated by the intricacies of diplomacy, more inclined, perhaps, to brandish military power. But in the Clinton years, these did not loom large. He knew the senator far better than he knew Bush — who was pretty much a blank on national-security issues anyway — and admired him, above all, for his readiness to take lonely stands.

He was sitting with McCain when the South Carolina primary returns came in following a campaign in which McCain's mental stability was questioned and calls were made to likely Republican voters telling them the former P.O.W. and his wife had a black baby, without mentioning that the little girl had been adopted at an orphanage in Bangladesh. Reached by Don Walton, the respected political reporter of The Lincoln Star Journal, Hagel said Bush had "sold his soul to the right wing." He called it "the filthiest campaign I've ever seen."

"I'd say the same thing today," he said when I asked about South Carolina, nearly six years later.

Considering how he'd disappointed Bush after the attention lavished on him in Austin and what he'd said about South Carolina, it's remarkable that Senator Hagel then found himself on the short list for running mate in 2000. To this day, he doesn't know whether he was seriously in contention. Possibly there was some thought that the former member of the Texas Air National Guard could benefit by picking, or at least appearing to consider, a twice-wounded Vietnam vet. Hagel says he spent $15,000 on accountant fees assembling the information the campaign demanded. Dick Cheney, the chief talent scout, interviewed him twice and sent his son-in-law around to pick up a box of documents before it was discovered that the talent scout was actually the talent.

"I still have the box," Hagel said. Nothing could be more unanswerable than the question of what might have happened in Iraq had he been picked. It's a testament to the vice president's influence that it even occurs.

agel had been to Iraq four times by the time Cheney paid his first visit as vice president in December 2005. Today the war is so much in the front of the senator's mind that it pops into just about any answer he gives to a political question, sometimes more than once. When I asked whether he saw himself as a maverick, his reply boiled down to saying he was a consistent conservative. But here's how it began: "When I think of issues like Iraq, of how we went into it — no planning, no preparation, no sense of consequences, of where we were going, how we were going to get out, went in without enough men, no exit strategy, those kind of things — I'll speak out, I'll go against my party."

agel had been to Iraq four times by the time Cheney paid his first visit as vice president in December 2005. Today the war is so much in the front of the senator's mind that it pops into just about any answer he gives to a political question, sometimes more than once. When I asked whether he saw himself as a maverick, his reply boiled down to saying he was a consistent conservative. But here's how it began: "When I think of issues like Iraq, of how we went into it — no planning, no preparation, no sense of consequences, of where we were going, how we were going to get out, went in without enough men, no exit strategy, those kind of things — I'll speak out, I'll go against my party."

A minute later, still chewing on the same question, Hagel was relating the retort of a Nebraska friend to a Republican who'd complained that the senator was still out of step with the president. Pretty much the same litany then tumbled out as, speaking in what was supposed to be the friend's voice, Hagel went on: "Who's the conservative here? Who votes against the Medicare reform bill, who votes against No Child Left Behind, who votes against the farm bill, who's opposed to invading another country, occupying another country, with no plans, no exit strategy and not enough troops? Now you tell me who the conservative is."

The trouble with Iraq as an identifying issue for a potential candidate today is that practically everyone except Senator Russ Feingold of Wisconsin and Congressman John Murtha of Pennsylvania, who have flirted with the idea of a deadline for withdrawal, purports to be in essentially the same position with regard to what needs to be happen: hoping that the insurgency will wane, that the Sunnis will somehow be mollified, that the number of U.S. troops can be drawn down this year, that Iraqis will be able to finish the war, more or less on their own. Everyone, for the moment, includes George W. Bush, Hillary Clinton and Chuck Hagel. Some are more hopeful (Bush), and some decidedly less (Hagel). No one now can really know how Iraq will play out in our politics.

It's not, in any case, an issue on which Hagel can easily "position" himself the way most senators who are not satisfied with being senators would. As this least partisan Republican stews on his decision on whether to go national with his sense of frustration, he has to know that his independence and forthrightness, the qualities that so far have defined him, are also his most obvious limitations in the roughhouse game of presidential politics as we know it. A candidate who worries about the price he may have to pay for anything he says would not have called for active engagement with Iran and Cuba as Hagel has regularly done in foreign-policy speeches over the last several years. And he would probably not be displaying, as Hagel has recently done, a newfound sensitivity on civil liberties matters. Through the end of 2004, Hagel's rating on the legislative scorecard of the American Civil Liberties Union was an anemic 22 percent. But at the end of December, as Congress rushed to adjourn, he was one of only four Republican senators whose votes held up an extension of the Patriot Act, arguing for checks on federal powers to invade homes and private records that had passed the Senate unanimously but then had been dropped in conference.

"When government continues to erode individual rights, that's the most dangerous, dangerous threat to freedom there is," he said, calling it "far more dangerous than terrorism." His reaction was similarly sharp when he first heard of the report in this newspaper that the president had claimed authority to order domestic wiretapping without court approval. "If, in fact, this is true," he said, "then it needs to stop." When the White House acknowledged it was true, Hagel pressed for Congressional hearings and a national debate. "I think Congress has failed the country in many ways," he said at a forum in California last month. One way was to allow the administration "to completely overpower the debate based on, 'I'm the commander in chief, and I know what's best.' "

As he road-tests themes for a possible campaign, he argues that his party is running low on ideas for the country's future, so fixated has it been on the threat of terrorism and maintaining itself in power. The importance of terrorism can't be minimized, he hastens to say, but through neglect of research and infrastructure, through failures in education, the country is losing its edge in a competitive world economy. Sure, globalization causes dislocations, this devout free trader and new-economy entrepreneur says, and, sure, the rise of China presents problems, but these are facts of life "that we are not going to unwind." Forty-six years after a senator last made it directly to the White House, he gropes for words in which to talk about national purpose, about a Manhattan Project for alternate energy sources, about getting the country moving again. These themes are in the air; President Bush latched onto them in his State of the Union address in January.

Earlier in the month, Hagel had already tried them out at a breakfast talk to a conservative group in Orange County, Calif. The breakfast had opened with an invocation in which "the vision of a former lifeguard called Dutch" and the American engagement in Iraq had been gratefully cited as part of "God's plan" to spread freedom around the globe. That left Hagel sounding a little impious when he gave his cool assessment of the venture on the Euphrates. Iraq may yet work out, he said. "I don't think it will, but it may." But as for the conservative revolution in America, "Where," he asked, "is Phase 2?"

The audience — youngish businessfolk who had formed a new political action committee called Atlas, after Ayn Rand's paean to competitiveness, "Atlas Shrugged" — seemed mildly appreciative rather than shocked.

"This administration has kept America on such a narrow ledge," he remarked after the talk. "Everything is terrorism."

In Washington, I asked Senator McCain whether he saw his pal next door as a serious candidate in 2008. The senator, who rode a campaign bus he called the Straight Talk Express in 2000, knows something about the advantages and disadvantages of candor in a national campaign. In this instance he either misconstrued or sidestepped my question. He replied that Hagel was definitely serious, one of the two, three or four leading voices on national security and foreign policy in the Senate. "Chuck really works at it," he said.

McCain was an early enthusiast for the war in Iraq, Hagel an early skeptic. Could he imagine the co-chairman of his first national race having a place on a McCain ticket or in a McCain administration? I asked. "I'd be honored to have Chuck with me in any capacity," McCain replied. "He'd make a great secretary of state."

Propriety and common sense argue that it's too early to place such bets. Hagel isn't ready to have the conversation with McCain that he knows he'll have to have. He's still at the stage of testing audience responses, of looking into faces to see if they give back any hint of encouragement, even recognition. "Hello," he'll say, sticking out his hand to a receptionist or a registration clerk, "I'm Senator Chuck Hagel." He has done it often enough to know that the likely response is a blank stare, but still he persists as he travels beyond Washington and Nebraska, to Los Angeles, New York, Iowa, New Hampshire, even McCain territory — he had a fund-raiser in Phoenix last month — trying to identify potential donors and supporters.

Whatever he concludes, he promises he'll go on saying what he thinks a senator should say about issues as they arise. "I don't have to be president; I don't have to be a senator," he said over dinner in an Omaha steakhouse. "I have to live with myself." More striking than the words was the urgency with which he spoke them. He seemed to be speaking more to himself than his companions, as if repeating a vow. Of course, we know, or think we know, that people who don't have to be president are unlikely to get the chance.

No comments:

Post a Comment